Greetings and salutations, Hivers.

Let’s talk about the oddball of American currency: the $2 bill.

If you live in the United States, chances are you haven’t seen one in a while, if ever. And if you have, you may have hesitated to spend it, unsure if it was still legal tender or worried that some poor cashier would eye you like you’d tried to pass off Confederate money. Even if you didn’t worry that, you may have decided it was rare enough to save, just on the odd chance it may be worth something to a collector.

Yet the $2 bill is not only legal and current, it’s also one of the most misunderstood and underused pieces of US currency. Let’s take a look at where this unusual note came from, why it’s (mostly) disappeared from everyday use, and how it’s doing today.

A Brief History of the Deuce

The $2 bill was first issued in 1862, right in the middle of the Civil War, as part of the original batch of legal tender notes known as “greenbacks”. At that time, it featured Alexander Hamilton, long before he would move to the $10 where he still is today.

By 1869, Hamilton had been swapped out for Thomas Jefferson, and it’s been Jefferson ever since. Over the decades, the design changed multiple times, but it always remained the awkward middle child between the $1 and the $5.

That awkwardness wasn’t just psychological—it was also systemic. At the time, the US still circulated gold coins, and there was already a denomination that filled the space between $1 and $5: the $2.50 gold coin, also known as the quarter eagle. Introduced in the late 18th century, the quarter eagle was a well-established part of the currency system and made the $2 note feel a bit redundant, or at least a bit off. To help you understand that, just imagine the US introduced a 20 cent bill today. It’d be a little strange, wouldn’t it? Why use it when there is the quarter? The $2 bill to the quarter eagle was something of the same.

Later, when the gold coins were phased out, the $2 still failed to find its niche. Why?

A few reasons:

- Low utility: Most everyday transactions called for $1s at the most, and even if something did go over one, using two $1s was just as convenient if not more so than searching for a $2.

- Superstition: Some gamblers and election-day regulars considered $2 bills unlucky. Others associated them with bribery.

- Confusion: People just didn’t see them much, so when they did, they weren’t sure they were real.

By 1966, the Treasury gave up and discontinued the bill altogether. But that wasn’t the end.

The Bicentennial Reboot

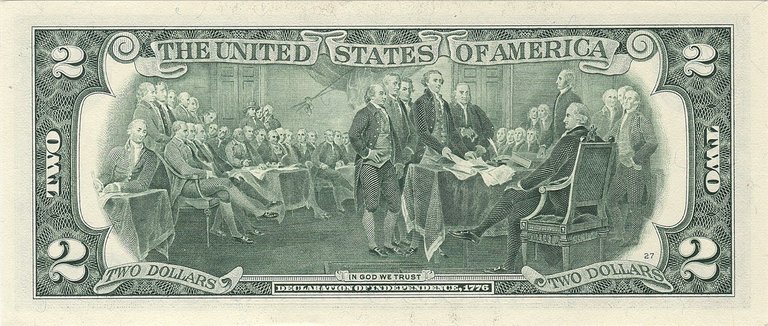

In 1976, the $2 bill was revived in honor of the United States Bicentennial. The new version had a fresh reverse image: not the usual Jefferson home of Monticello, but a reproduction of John Trumbull’s painting of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. This dramatic, historical tableau is often mistaken for the signing of the Constitution (a different painting entirely), but its presence on the bill was meant to tie the note to America’s founding ideals.

It really is a very attractive design. Look:

via Wikipedia

The most attractive front side of a bill would probably be the $100, but I think this one takes the cake for the most attractive back.

The Treasury hoped that reintroducing the $2 would reduce the number of $1s printed and save money. But once again, the public didn’t bite. It looked strange, it wasn’t dispensed in ATMs, and most banks didn’t stock them unless requested.

Instead of entering wide circulation, the $2 bill became a collector’s item—ironic, since it was intended to be boringly practical.

Is It Still Printed?

Yes. Contrary to popular belief, $2 bills are still being printed by the Bureau of Engraving and Printing. They just aren’t printed every year. The Federal Reserve prints them in batches when banks request them, which is infrequent due to low demand.

As of 2024, about $2.8 billion worth of $2 bills are in circulation or hoarded away in drawers and collector albums. That’s not much compared to the $1 or $20, but it’s far from extinct.

Can You Spend Them?

Absolutely. Every $2 bill printed since 1976 is legal tender. But that doesn’t mean you won’t run into trouble. Some cashiers might raise an eyebrow. Some may call a manager. A few may outright refuse to accept it—not out of malice, but simply because they’ve never handled one before.

This has led to all sorts of amusing—and occasionally infuriating—stories. One man was detained by police because a store clerk thought his $2 bills were counterfeit. He was later vindicated, of course, but the incident shows just how strange this very real piece of currency seems to most Americans.

If you are like me, you embrace this. When I was in the US, I always asked banks you give me as many $2 bills as they had when I cashed my paycheck. They were fun to spend for exactly that reason. There’s a small group of people who feel the same, but it’s not large enough to make any real dent in their usage.

Should You Use Them?

Why not? Like I wrote above, I used to like to get them from the bank and use them specifically because they are uncommon and would provoke interesting reactions. When I first came to Japan I used to like to do the same with the ¥2000 note, which is also quite uncommon.[1]

Spending $2 bills is a great way to remind people that this quirky part of our monetary history is still alive. Plus, it often sparks conversations—sometimes confused, sometimes delighted.

If enough of us used them, they might stop being so weird. Then again, maybe the weirdness is the best part.

So—do you use $2 bills? Have any good stories about spending one? Or did you, like many, think they were long gone? Let me know in the comments.

❦

-

It’s become even more rare in the years since, so I can’t really do this anymore. But I still do it with $2 bills when I visit the States. ↩