On May 25, 1334, a boy was born into chaos. He would be raised as emperor, rule in exile, and later be remembered not as a sovereign but a pretender. That boy would become Emperor Sukō (崇光天皇), the third of the so-called "Northern Court emperors" backed by the Ashikaga shogunate during Japan’s split dynastic era known as the Nanboku-chō (南北朝, Northern and Southern Courts) period.

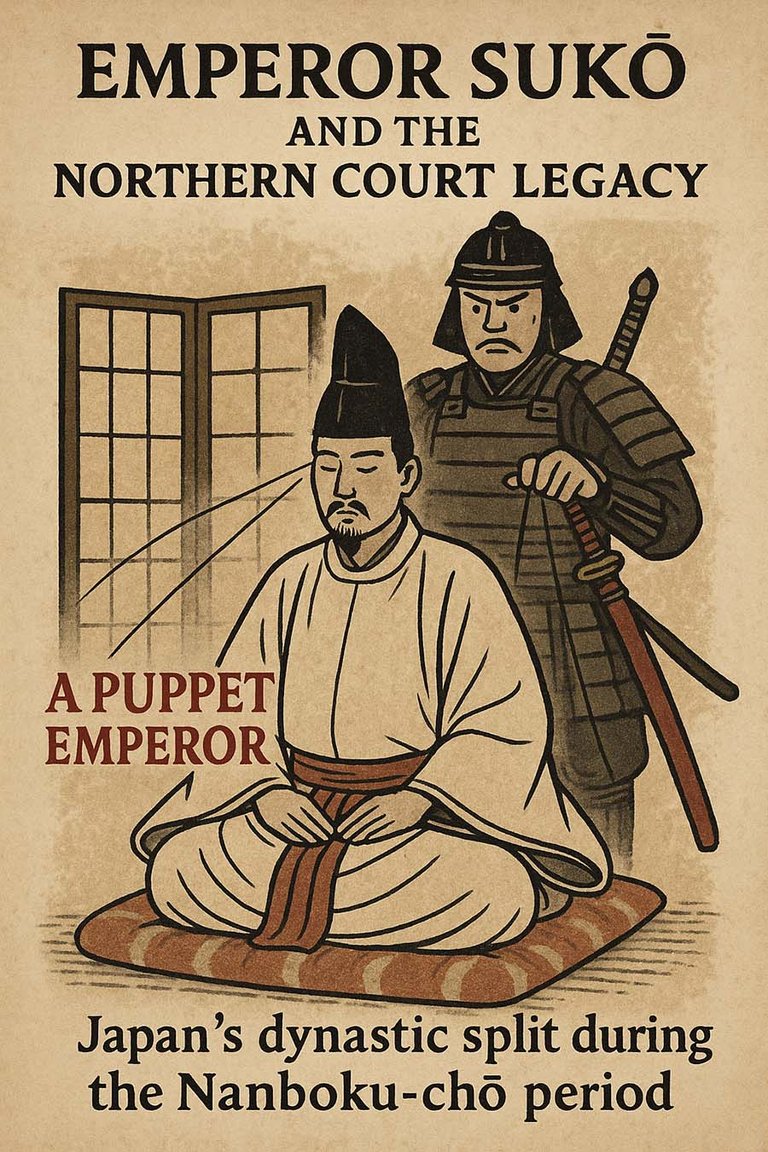

If you’ve never heard of Emperor Sukō, don’t feel bad. Most Japanese haven’t either. His name is tucked away in dusty chronicles because the very legitimacy of his rule — along with the rest of the Northern Court — was disavowed by imperial decree in the Meiji era. Officially, only the Southern Court emperors are considered "legitimate." Sukō and his Northern peers were relegated to the status of tōgō (統合) emperors: basically figureheads installed by military force.

But, as always, the story is more complicated than a simple matter of legitimacy.

The Fractured Court

The split began with Emperor Go-Daigo’s failed attempt to wrest power back from the Kamakura shogunate. After his brief success in the Kemmu Restoration (1333–1336), he was overthrown by Ashikaga Takauji, a former ally who set up a rival emperor in Kyoto. Thus began the Nanboku-chō jidai, a dynastic civil war that lasted from 1336 to 1392, with one emperor in Yoshino (the Southern Court, backed by loyalists to the old imperial line) and another in Kyoto (the Northern Court, backed by the Ashikaga).

Confused yet? Basically the Southern Court was supported by the old aristocracy who wanted to return to the old way (where they controlled the Emperor) and the Northern Court was supported by the Shogunate who wanted a loyal Emperor to do whatever they ordered. In both cases, the Emperor would be controlled. There is a reason that historically being Emperor in Japan has been likened to being imprisoned in a golden cage.

Sukō ascended the Northern throne in 1348 at just 14 years old, following the abdication of his uncle Emperor Kōmyō. His reign was short-lived (lasting just three years, until 1351) when a temporary reconciliation between the two courts led to his forced abdication. The Ashikaga hoped to unify the court under a Southern emperor, but the peace fell apart within a year.

Sukō’s removal marked the beginning of political turbulence even within the Northern Court itself. His own brother would later become Emperor Go-Kōgon, and Sukō’s son attempted to stake a claim to the throne, resulting in further factionalism among Northern loyalists.

The Ashikaga’s Puppet?

Though Sukō held the throne, it’s clear who pulled the strings. The Ashikaga shoguns (particularly Takauji) needed an emperor to legitimize their rule, but had no intention of ceding real power. Sukō was a symbol of that strategy: a child on the throne, a court with no real autonomy, and a dynasty backed not by divine right, but by military might.

Historical Footnote

In 1911, Emperor Meiji’s government ruled that only the Southern Court emperors, descended from Go-Daigo, had rightful claim to the Chrysanthemum Throne. This reshaped Japanese historical understanding, elevating figures like Emperor Go-Murakami while relegating the Northern emperors (Sukō included) to the margins.

Interesting, this episode of history came up again after WWII. A fellow named Kumazawa Hiromichi (熊沢寛道) claimed descent from the Southern line and he declared Emperor Shōwa (Hirohito) as descended from the Northern Court. He therefore proclaimed himself the true emperor and petitioned the Japanese government and US Occupation to strip Shōwa of all power and recognize him. He was mostly ignored. Technically he was correct — Shōwa was descended from the Northern Court — but since the two lines merged after 1392, all modern emperors are descended from both lines.

But I digress. That's actually a really interesting episode, so I may write another post about it later.

Anyway, Sukō's existence reminds us that history is often a story written by the victors, as Napoleon once told us. On this day, May 25, it’s worth remembering the boy born into the center of a nation’s constitutional fracture. He may not be counted in the official imperial line anymore, but for a few short years, he wore the crown of Japan.

❦

|

David is an American teacher and translator lost in Japan, trying to capture the beauty of this country one photo at a time and searching for the perfect haiku. He blogs here and at laspina.org. Write him on Mastodon. |