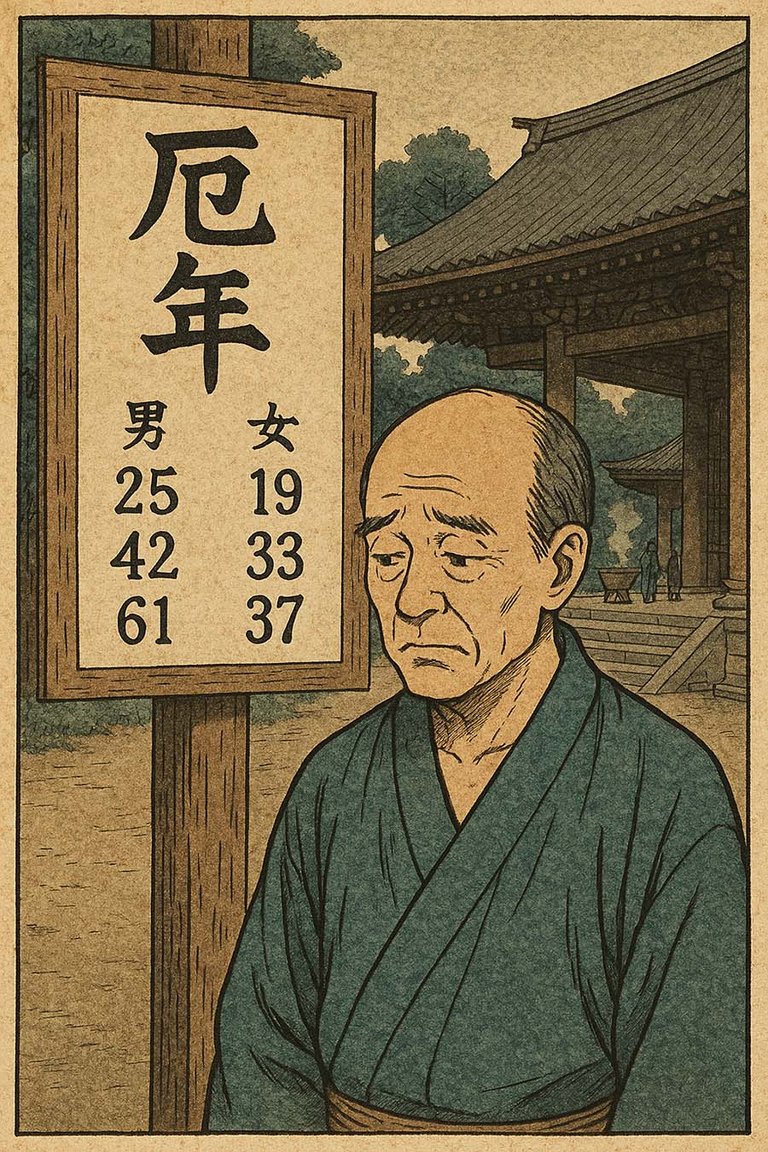

In Japan, there’s a concept called yakudoshi (厄年), usually translated as “unlucky years” or “calamitous ages”. It’s one of those quietly ever-present beliefs—not shouted from rooftops, but woven into the background fabric of life. And once you know about it, you’ll start noticing it everywhere: in temple rituals, at New Year’s shrine visits, even in the way people hesitate about certain birthdays.

So what exactly is yakudoshi, and should you be worried?

What Are the Yakudoshi Years?

Traditionally, three ages are considered especially unlucky:

- For men: 25, 42, and 61

- For women: 19, 33, and 37

The middle age in each set — 42 for men and 33 for women — is considered the most dangerous. Coincidentally, the word for 42 in Japanese is composed of shi-ni (四二), which can sound like “to death” (死に). Likewise, 33 is sometimes linked to san-zan (散々), meaning “terrible” or “disastrous”.

These beliefs aren’t just old superstitions buried in books. Even today, many Japanese people—especially those raised with more traditional or Shinto-influenced values—take them seriously. And when I say seriously, I mean you’ll find 42-year-old men lining up at temples for purification rituals.

The Maeyaku and Atoyaku

Here’s where it gets more elaborate.

Each yakudoshi year is bracketed by two additional “danger zones”:

- Maeyaku (前厄): the year before the unlucky one

- Atoyaku (後厄): the year after

So in total, each unlucky year becomes a three-year span of misfortune. That means if you’re a man hitting 42, you’ve actually got to worry about 41, 42, and 43. The same for women turning 33.

This explains why you’ll often see yakuyoke (厄除け, “bad luck prevention”) talismans for sale or special blessings being offered for people in these years. In fact, some temples post large signs near New Year’s that list the current yakudoshi ages by birth year so people know whether to come in for a ritual.

So Where Did This Come From?

The origin of yakudoshi is a bit murky.

Some scholars trace it back to ancient Chinese cosmology and numerology, where odd-numbered ages were associated with danger or imbalance. Others point to native Japanese beliefs around age transitions and physical maturation.

The logic is sometimes practical: age 42 might coincide with midlife stress, job changes, or health problems. For women, age 33 often aligns with childbearing stress and hormonal changes. There’s a sort of folk-scientific logic beneath the surface.

But over the centuries, whatever its origin, it became canonized into temple rites and woven into how people think about aging.

What People Do About It

There’s no official rulebook, but some common responses to yakudoshi include:

- Visiting a temple or shrine to receive a yakuyoke blessing

- Buying protective charms

- Avoiding major life changes during those years (e.g., starting a company or getting married)

- Holding a special party or gathering to “ward off” the bad luck

- Donating to temples or shrines — just in case

You’ll also hear stories of people who had terrible luck during their yakudoshi and are now firm believers. Others laugh it off entirely. Like many things in Japan, it lives in that gray zone between tradition and modernity — where you don’t really believe in it, but you don’t exactly want to test it either.

Should You Believe It?

Maybe not in a literal sense. But then again, even in the West, we have “milestone” years people dread—turning 40, or 30, or retiring at 65. And astrology, with its Mercury-in-retrograde panic cycles, has never exactly gone away either.

What yakudoshi offers, perhaps, is a built-in moment to pause and reflect. A reminder that some years are harder than others. That there’s value in rituals, even if they don’t have scientific backing. That we all sometimes need to step out of our usual rhythm and ask: Am I doing okay?

There’s something healthy, even grounding, about acknowledging those transitions. Even if you don’t buy the metaphysics, the ritual itself can serve a purpose.

Final Thoughts

I’ve always found these old Shinto ideas and rituals fascinating. They are the kinds of things that most people will say they don’t believe in and will dismiss as superstition nonsense, yet things the same people will still follow and do, ostensibly for fun and because of tradition, but some admit it’s because of “just in case”.

I sometimes join in — sometimes not. It often depends on if I have time, if I have money (these charms at shrine are expensive), or if I even remember. For my 42nd year I had intended to go do the shrine thing, but then I completely forgot at first and then just never got around to it. Finally one of my students actually bought me a charm because she was worries about me.[1] If memory serves, I did go to the shrine and buy a charm for my 41st year, but didn’t do anything for my 43rd. I don’t remember any terrible luck hitting me. Hmmm.

I’m a ways from my 61st, but when it comes will I do anything? Maybe. You know — just in case.

-

She was an old women. Older people do tend to believe these things more than young folks. ↩