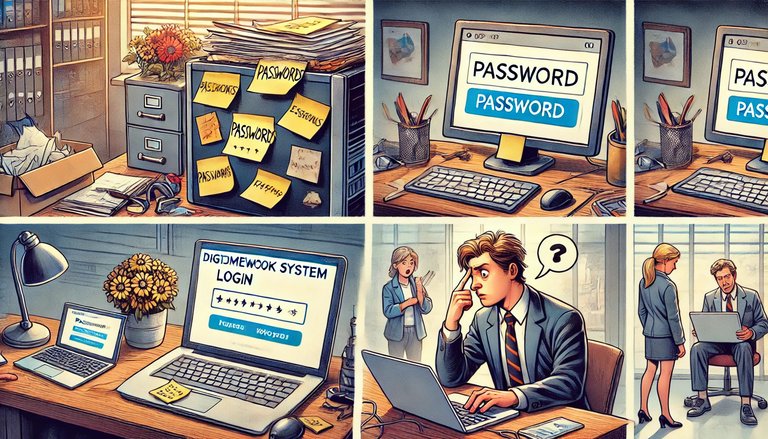

One of the side jobs I had while I was in university was as a system admin for a regional supermarket. I managed the mainframe, price updates, and that kind of thing. One thing I also managed was the local network for the workstations. I know it is stereotype at this point, but you'd be amazed at the bad password habits. Simple words like "password" or "mypassword", more complex passwords taped to the bottom of the keyboard or just written on a sticky note stuck on the monitor, and so on. All the crazy things you've read about are true, or were anyway. If they still are or not, I don't know. We could ask @bozz about that.

At the first company I worked for in Japan, they had a system for sending secure information. They would zip it up with a password and email it. Then they would send a second email with just the password and nothing else. I later learned that this is a fairly common method for sending secure information at many Japanese companies. To this day, I run into this method. The first time I ran into this, I pointed out that it's really not a very good security practice, but I was told that's the way things are and we can't change them. That's kind of a standard answer in Japan to anything. Change is slow and the usual answer is we do things as they have always been done regardless of whether the way they've always been done is good or bad.

Not long ago my kids' elementary school moved to a digital system for giving out homework. How it works is they give all the parents both email accounts and accounts in the homework system, one for each kid, so I ended up with four accounts.

That wouldn't be terribly confusing in my system, actually, because I use 1password, which manages all my usernames and passwords and syncs to all my devices, so I never have to worry about forgetting a password.

In this case, however, I needn't have worried: because all four accounts use the exact same password, which is only five digits plus a year. You can bet I immediately tried to change the passwords, figuring that maybe these were placeholders and were meant to be changed to better ones, but no... there is no way to change them, a fact I confirmed when I contacted the school about it.

More complex passwords and different passwords, I was told, would be too difficult for the parents. But, I countered, when you use a simple password and the same one for everything, it's trivial for a hacker to steal everyone's info. Why would anyone do that? No one wants student info, I was told.

Arguing more would have produced no result except attempts to get the difficult foreigner to shut up and leave them alone. I've been in these situations enough to know how it is.

It is as it is, I suppose. Or, in a Japanese phrase so common that even foreigners who otherwise don't speak the language immediately learn. shou ga nai (or shikata ga nai)—it can't be helped.

I have long been arguing for the past eight years that the Hive signup process is too complex and that a password and four long keys is too confusing to new users. Many haven't agreed with me over the years. Many others have agreed but have responded basically with shou ga nai.

Given the stories I list above, maybe you can see some of why I tend to think this.

❦

|

David LaSpina is an American photographer and translator lost in Japan, trying to capture the beauty of this country one photo at a time and searching for the perfect haiku. He blogs here and at laspina.org. Write him on Twitter or Mastodon. |